Hernando de Soto

| Hernando de Soto | |

|---|---|

Hernando de Soto |

|

| Born | c.1496/1497 either in Barcarrota or Badajoz, Spain |

| Died | May 21, 1542 (aged 45 or 46) Indian village of Guachoya (near present-day McArthur, Desha County, Arkansas) |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | explorer and conquistador |

| Religion | Roman Catholic Church |

| Signature | |

|

|

Hernando de Soto (c.1496/1497–1542) was a Spanish explorer and conquistador who, while leading the first European expedition deep into the territory of the modern-day United States, was the first European documented to have crossed the Mississippi River.[1]

A vast undertaking, de Soto's North American expedition ranged throughout the southeastern United States searching for gold and a passage to China. De Soto died in 1542 on the banks of the Mississippi River in Arkansas or Louisiana.

Hernando de Soto was born to parents who were hidalgos of modest means in Extremadura, a region of poverty and hardship from which many young people looked for ways to seek their fortune elsewhere. Two towns—Badajoz and Barcarrota—claim to be his birthplace. All that is known with certainty is that he spent time as a child at both places, and he stipulated in his will that his body be interred at Jerez de los Caballeros, where other members of his family were also interred.[2] The age of the Conquerors came on the heels of the Spanish reconquest of the Iberian peninsula from Islamic forces. Spain and Portugal were filled with young men begging for a chance to find military fame after the Moors were defeated. With discovery of new lands to the west (which seemed at the time to be East Asia), the whispers of glory and wealth were too compelling for the poor.

De Soto sailed to the New World in 1514 with the first Governor of Panama, Pedrarias Dávila. Brave leadership, unwavering loyalty, and clever schemes for the extortion of native villages for their captured chiefs became de Soto's hallmark during the Conquest of Central America. He gained fame as an excellent horseman, fighter, and tactician, but was notorious for the extreme brutality with which he wielded these gifts.

During that time, Juan Ponce de León, who discovered Florida, Vasco Núñez de Balboa, who discovered the Pacific Ocean (he called it the "South Sea" below Panama), and Ferdinand Magellan, who first sailed that ocean to the Orient, profoundly influenced de Soto's ambitions.

Contents |

First expedition – The Conquest of Peru

In 1530, de Soto became a regidor of León, Nicaragua. He led an expedition up the coast of the Yucatán Peninsula searching for passage between the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean to enable trade with the Orient, the richest market in the world. Failing that, and without means to further explore, de Soto, upon Dávila's death, left his estates in Nicaragua. Bringing his own men on ships he hired, de Soto joined Francisco Pizarro at his first base of Tumbez shortly before departure for the interior of Peru.

| Part of the series on Spanish colonization of the Americas |

|

| History of conquest |

| Inter caetera |

| Pacific Northwest |

| California |

| Colombia |

| Florida |

| Guatemala |

| Aztec Empire |

| Inca Empire |

| Yucatán |

| Conquistadores |

| Diego de Almagro |

| Pedro de Alvarado |

| Vasco Núñez de Balboa |

| Sebastián de Belalcázar |

| Francisco Vásquez de Coronado |

| Hernán Cortés |

| Luis Carvajal de la Cueva |

| Juan Ponce de León |

| Francisco de Montejo |

| Pánfilo de Narváez |

| Juan de Oñate |

| Francisco de Orellana |

| Francisco Pizarro |

| Hernando de Soto |

| Pedro de Valdivia |

Pizarro immediately made de Soto one of his captains. When Pizarro and his men first encountered the army of the Inca Atahualpa at Cajamarca, Pizarro sent de Soto with fifteen men to invite Atahualpa to a meeting. When Pizarro's men attacked Atahualpa and his guard the next day (the Battle of Cajamarca), de Soto led one of the three groups of mounted soldiers. The Spanish captured Atahualpa. De Soto was sent to the camp of the Incan army, where he and his men plundered Atahualpa's tents.[3]

During 1533, the Spanish held Atahualpa captive in Cajamarca for months while a room was filled with gold and silver objects to ransom him. During this captivity, de Soto became friendly with Atahualpa, and taught him to play chess. By the time the ransom had been completed, the Spanish became alarmed by rumors of an Incan army advancing on Cajamarca. Pizarro sent de Soto with four men to scout for the rumored army.

While de Soto was gone, the Spanish in Cajamarca decided to kill Atahualpa to prevent his rescue by the Incan army. De Soto returned later to report that he could find no signs of an army in the area. After executing Atahualpa, Pizarro and his men headed to Cuzco, the capital of the Incan Empire. As the Spanish force approached Cuzco, Pizarro sent his brother Hernando and de Soto ahead with forty men. The advance guard fought a pitched battle with Incan troops in front of the city, but the battle had ended before Francisco Pizarro arrived with the rest of the Spanish party. The Incan army withdrew during the night. The Spanish plundered Cuzco, where they found much gold and silver. Receiving a mounted soldier's share of the plunder from Atahualpa's camp, Atahualpa's ransom, and the plunder from Cuzco, de Soto became very wealthy.[4]

On the road to Cuzco, Manco Inca Yupanqui, a brother of Atahualpa, had joined Pizarro. Manco had been hiding from Atahualpa in fear of his life, and was happy to place himself under Pizarro's protection. Pizarro arranged for Manco to be installed as the Inca leader. De Soto joined Manco in a campaign to eliminate the Incan armies who had been loyal to Atahualpa. By 1534, de Soto was serving as lieutenant governor of Cuzco while Pizarro was building his new capital (which later became known as Lima) on the coast. In 1535 King Charles awarded Diego de Almagro, Francisco Pizarro's former business partner, the governorship of the southern portion of the Incan Empire. Pizarro and de Almagro quarreled over which governorship Cuzco was in. When de Almagro made plans to explore and conquer the southern part of the Incan empire (Chile), de Soto applied to be his second-in-command, offering a large payment for the position, but de Almagro turned him down. De Soto packed up his treasure and returned to Spain in 1534.

Return to Spain

De Soto returned to Spain with an enormous share of the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire. Famous for being the hero of that conquest, he was admitted into the prestigious Order of Santiago. His share was awarded to him by the King of Spain, and he received 724 marks of gold, 17,740 pesos.[5] He married Isabel de Bobadilla, daughter of Pedrarias Dávila and a relative of a confidante of Queen Isabella. De Soto petitioned King Charles for the government of Guatemala "with "permission to make discovery in the South Sea", but was granted the governorship of Cuba instead. De Soto was expected to colonize the North American continent for Spain within four years, for which his family would be given a sizeable piece of land.

Fascinated by the stories of Cabeza de Vaca, Spain's just-returned North American explorer, de Soto selected 620 eager Spanish and Portuguese volunteers, some of African descent, for the governing of Cuba and conquest of North America. Averaging 24 years of age, they eventually embarked from Havana on seven of the King's ships and two caravels of de Soto's. With tons of heavy armour and equipment, the livestock count came to over 500, including 237 horses and 200 pigs for their four-year continental search.

De Soto's exploration of North America

Historiography

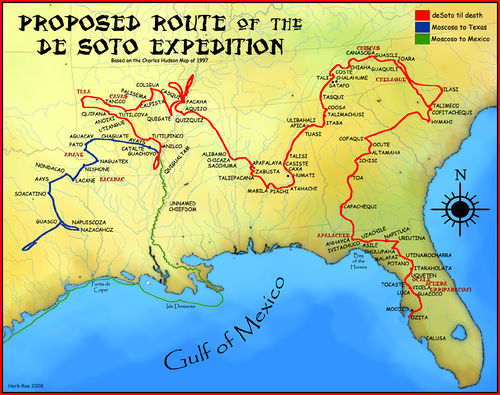

The main course of de Soto's expedition is subject to discussions and controversy among historians and local politicians. The most widely used version of De Soto's Trail comes from a study commissioned by the Congress of the United States. A committee chaired by the anthropologist John R. Swanton published "The Final Report of the United States De Soto Expedition Commission" in 1939. Among other locations, Manatee County, Florida, claims an approximate landing site for de Soto and has a national memorial recognizing the event.[7] The first part of the expedition's course until de Soto's battle at Mabila in Alabama) is disputed only in minor details today; yet de Soto's trail beyond Mabila is contested. Swanton reported the de Soto trail ran from there through Mississippi, Arkansas and Texas. Other theories have argued for a northern route through Tennessee, Kentucky and Indiana from Mabila.

HIstorians have more recently considered archeological reconstructions and the oral history of Native Americans. Most historical places have been overbuilt, however, and more than 450 years have passed between the events and current history tellers. The only site definitively associated with de Soto's expedition is the Governor Martin Site at the Apalachee village of Anhaica, located about a mile east of the present Florida Capitol in Tallahassee, Florida. It was found by archaeologist B. Calvin Jones in March 1987. Many archaeologists believe the Parkin Site in Northeast Arkansas was the main town for the province of Casqui, which de Soto noted. They base this on similarities between descriptions from the journals of the de Soto Expedition and artifacts of European origin discovered at the site in the 1960s.[8][9]

The latest theory draws a route based on accounts from two journals of de Soto exploration survivors: de Soto's Secretary, Rodrigo Ranjel, and the King's agent with de Soto, Luys Hernández de Biedma. They described De Soto's Trail in relation to Havana, from which they sailed; the Gulf of Mexico, which they skirted inland then later headed back toward; the Atlantic Ocean, which they approached during their second year; high mountains, which they traversed immediately thereafter; and dozens of other geographic features along their way - large rivers and swamps - at recorded intervals. Given that the Earth's natural geography has not changed since de Soto's time, those journals have been analyzed with modern topographic intelligence, to render a more precise De Soto Trail.

1539 to early-1540 in Florida

The Spanish caption reads:

"HERNANDO DE SOTO: Extremaduran, one of the discoverers and conquerors of Peru: he travelled across all the Florida and defeated its still invincible natives, he died in his expedition in the year of 1543 at the 42 of his age".

In May 1539, de Soto landed nine ships with over 620 men and 220 surviving horses at present day Shaw's Point, in Bradenton, FL. He named it Espíritu Santo after the Holy Spirit. The ships brought priests, craftsmen, engineers, farmers, and merchants; some with their families, some from Cuba, most from Europe and Africa. Few of them had ever traveled outside of Spain, or even their home villages.

A Spaniard named Juan Ortiz, who had come to Florida with the failed Narváez Expedition and been held by an inland tribe, was sighted near de Soto's port. Ortiz came to Florida in search of the earlier Narváez Expedition and was captured by the Uzita.[10] The daughter of Chief Hirrihigua of the Uzita reportedly begged for Ortiz's life, as her father had ordered Ortiz to be roasted alive. Ortiz survived captivity and torture, and quickly joined the new de Soto expedition. Ortiz knew the countryside and also helped as an interpreter.

As a lead guide, Ortiz established a unique method for guiding the expedition and communicating with various tribal dialects. He recruited Paracoxi guides from each tribe along the route. A chain of communication was established whereby a guide who had lived in close proximity to another tribal area was able to pass his information and language on to a guide from a neighboring area. Because Ortiz refused to dress and conduct himself as a hidalgo Spaniard, other officers questioned his motives and counsel to de Soto. De Soto remained loyal to Ortiz, thus allowing him the freedom to dress and live among his Paracoxi friends. Another important guide was the seventeen-year-old boy Perico, or Pedro, from modern-day Georgia. He spoke several of the local tribes' languages and could communicate with Ortiz. Perico was taken as a guide in 1540 and treated better than the rest of the slaves, due to his value to the Spaniards.

The expedition traveled north, exploring Florida's West Coast, encountering native ambushes and conflicts along the way. De Soto's first winter encampment was at Anhaica, the capital of the Apalachee. It is one of the few places on the route where archaeologists have found physical traces of the expedition. It was described as being near the "Bay of Horses", where members of the preceding Narváez expedition killed and ate their horses while building boats for escape.

1540 – In Georgia, the Carolinas, Tennessee, Alabama & Mississippi

From their winter location in the western panhandle of Florida, having heard of gold being mined "toward the sun's rising," the expedition turned north-east through what is now the modern state of Georgia. Recently archaeological finds were made at a remote, privately owned site near the Ocmulgee River in Telfair County. These included nine glass beads, some of which bear a chevron pattern believed to be indicative of the de Soto expedition. Six metal objects were also found, including a silver pendant and some iron tools.[11] The expedition continued on to present-day South Carolina. The expedition was received there by a female chief (Cofitachequi), who turned over her tribe's pearls, food and anything else the Spaniards wanted. The expedition found no gold, however, other than pieces from an earlier coastal expedition(presumably that of Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón.)

De Soto headed north into the Appalachian Mountains of North Carolina, where he spent a month resting the horses while his men searched for gold. De Soto then entered Tennessee and Northern Georgia, where he spent another month before turning south toward the Gulf of Mexico to meet two ships bearing fresh supplies from Havana.

Along the way, along a river in southern Alabama, de Soto was led into Mauvila (or Mabila), a fortified city.[12] The Mobilian tribe, under Chief Tuskaloosa, ambushed de Soto's army.[12] Other sources suggest de Soto's men were attacked after attempting to force their way into a cabin occupied by Tuskaloosa.[13] The Spaniards managed to fight their way out and retaliated by burning the city to the ground. During the nine-hour encounter, twenty Spaniards died, and most were wounded. Twenty more died during the next few weeks. The Native American warriors of that area—between 2,000 and 6,000 of them—died fighting in the fields, by fire in the city, or by suicide.

Even though the Spaniards "won" the battle, they lost most of their possessions and forty horses. The Spaniards were wounded, sickened, surrounded by enemies and without equipment in an unknown territory.[13] Fearing that word of this would reach Spain if his men reached the ships at Mobile Bay, de Soto led them away from the Gulf Coast, into Mississippi, most likely near present-day Tupelo, where they spent the winter.

1541 – To the west through Mississippi, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Louisiana & Texas

In the spring of 1541, de Soto demanded 200 men as porters from the Chickasaw. They refused his demand and attacked the Spanish camp during the night. The Spaniards lost about forty men and the remainder of their equipment. According to participating chroniclers, the expedition could have been destroyed. Luckily for the expedition, the Chickasaw let them go.

On May 8, 1541, de Soto's troops reached the Mississippi River (discovered by Alonso Álvarez de Pineda in 1519, who sailed twenty miles up the river).[1]

De Soto was less interested in this find though, recognizing it, first of all, as an obstacle to his mission. He and 400 men had to cross the broad river, which was constantly patrolled by hostile natives. After about one month, and the construction of several floats, they finally crossed the Mississippi at or near Memphis, Tennessee and continued their travels westwards through modern-day Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. They wintered in Autiamique, on the Arkansas River.

In 1541, the expedition became the first Europeans to see what Native Americans referred to as the Valley of the Vapors, Hot Springs, Arkansas. Members of many tribes had gathered at the valley over many years to enjoy the healing properties of the thermal springs. The tribes had developed agreements to put aside their weapons and partake of the healing waters in peace while in the valley. De Soto and his men stayed just long enough to claim the area for Spain.

After a harsh winter, the Spanish expedition decamped and moved on more and more erratically. Their interpreter, Juan Ortiz, had died, making it more difficult to find directions, food sources and communicate with the Natives in general. The expedition went as far inward as the Caddo River, where they clashed with a militant Native American tribe called the Tula, whom the Spaniards considered to be the most skilled and dangerous warriors they had encountered.[14] This possibly happened in the area of present-day Caddo Gap, Arkansas (a monument stands in that community). Eventually, the Spaniards returned to the Mississippi River.

De Soto's death

De Soto died of a semitropical fever on May 21, 1542, in the native village of Guachoya (historical sources disagree as to whether de Soto died near present-day MacArthur, Arkansas or in Louisiana)[15] on the western banks of the Mississippi.[16] Before his death, de Soto chose his former maestro de campo (roughly, field commander) Luis de Moscoso Alvarado to assume command of his expedition.[17]

Since de Soto had encouraged the local natives to believe that he was an immortal sun god (as a ploy to gain their submission without conflict), his men had to conceal his death. They hid his corpse in blankets weighted with sand and sank it in the middle of the Mississippi River during the night. Native Americans had already become skeptical of de Soto's deity claims.[15] Another possible location for his death is near present day Lake Village, Arkansas.

Return of the expedition to Mexico City

De Soto's expedition had explored La Florida for three years without finding the expected treasures or a hospitable site for colonization efforts. They had lost nearly half their men, most of the horses had been killed, they were wearing animal skins for clothes and many were injured and in poor health. The leaders came to a consensus (although not total) to abort the expedition and try to find a way home, either down the Mississippi River, or overland across Texas to the Spanish colony of Mexico City.

They decided that building boats would be too difficult and time–consuming, and that navigating the Gulf of Mexico too risky, so they headed overland to the southwest. Eventually they reached a region in present-day Texas that was dry. The native populations had thinned out to subsistence hunter-gatherers, which presented a serious problem as there were no villages to raid for food and the army was too large to live off the land. They were forced to backtrack to the more developed agricultural regions along the Mississippi. There they began building seven bergantínes, or brigantines.[17] They melted down all the iron they had, including horse tackle and slave shackles, to make nails for the boats. Winter came and went and the spring floods delayed another two months, but by July they set off down the Mississippi for the coast. Taking about two weeks to make the journey, the expedition encountered hostile tribes along the whole course. Natives would follow the boats in canoes and shoot arrows at the men sometimes for days on end as they drifted through their territory. The Spanish had no effective offensive weapons on the water as their crossbows had long ceased working. They relied on armor and sleeping mats to block the arrows. About 11 Spaniards were killed along this stretch and many more wounded.

On reaching the mouth of the Mississippi, they stayed close to the Gulf shore heading south and west. After about 50 days, they made it to the Pánuco River and the Spanish frontier town of Pánuco. There they rested for about a month, during which time many of the Spaniards, having safely returned and reflecting on their accomplishments, decided they had left La Florida too soon, leading to fights and some deaths. However, after they continued on to Mexico City and Viceroy Don Antonio de Mendoza offered to lead another expedition back to La Florida, few volunteered. Out of the initial 700 participants, somewhere between 300 and 350 survived (311 is a commonly accepted figure.) Most of the men stayed in the New World, settling in Mexico, Peru, Cuba and other Spanish colonies

Effects of expedition in North America

De Soto's excursion to Florida was a failure from the point of view of the Spanish. They acquired neither gold nor prosperity and founded no colonies. The reputation of the expedition, at the time, was more like that of the later Don Quixote than that of Hernán Cortés. Nonetheless, it had several major consequences.

On one hand, the expedition left its traces in the areas they traveled through. Some of the swine, brought by de Soto, escaped and were the ancestors of razorback pigs in the southeastern United States. De Soto was instrumental in contributing to a hostile relationship between some Natives and Europeans.

When his expedition encountered hostile Natives in the new lands, more times than not, his men instigated the clashes.[18]

More devastating than the battles, however, were the diseases carried by the members of the expedition. Because they lacked immunity to Eurasian diseases, the indigenous people suffered epidemic illnesses after contracting infectious diseases, such as measles, smallpox and chicken pox. Several areas which the expedition crossed became depopulated by disease caused by contact with the Europeans. Many natives fled the populated areas which had been struck by the illnesses and went towards the surrounding hills and swamps. In some areas, the social structure changed because of losses to epidemics.[19]

The records of the expedition contributed greatly to European knowledge about the geography, biology and ethnology of the New World. The de Soto expedition's descriptions of North American natives are the earliest-known source of information about the societies in the Southeast. They are the only European description of North American native habits before the natives encountered other Europeans. De Soto's men were both the first and nearly last Europeans to experience the Mississippian culture.

De Soto's expedition led the Spanish crown to reconsider Spain's attitude towards the colonies north of Mexico. He claimed large parts of North America for Spain. They concentrated their missions in the state of Florida and along the Pacific coast.

Namesakes

Many places were named after de Soto:

- De Soto County, Mississippi (where he allegedly died), the county seat Hernando, De Soto Parish, Louisiana, and both De Soto and Hernando County in Florida.

- Fort De Soto Park at the far southern tip of the city of St. Petersburg, Florida and DeSoto State Park in Alabama.

- The place of his disembarkation, Espiritu Santo, Florida, is marked by the De Soto National Memorial west of Bradenton, Florida.

- The De Soto School is a private school in Helena, Arkansas.

- Also named after him was the American automobile, the DeSoto.

Sites visited by the de Soto expedition

- List of sites and peoples visited by the Hernando de Soto Expedition

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Morison, Samuel (1974). The European Discovery of America: The Southern Voyages, 1492-1616. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Charles Hudson (1997). Page 39.

- ↑ MacQuarrie. Pp. 57-68, 71-2, 91-2.

- ↑ MacQuarrie. Pp. 96, 106, 135, 138, 145, 169.

- ↑ Von Hagen, Victor W., 1955, American Heritage, "De Soto and the Golden Road", August 1955, Vol.VI,No.5, American Heritage Publishing, New York, pp.102-103.

- ↑ Hudson, Charles M. (1997). Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun. University of Georgia Press.

- ↑ Manatee County History, Manatee Florida Chamber of Commerce.

- ↑ "The Parkin site: Hernando de soto in cross county, Arkansas" (PDF). http://www.uark.edu/campus-resources/archinfo/parkin_site.pdf. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ↑ "Parkin Archeological State Park-Encyclopedia of Arkansas". http://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=1246. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

- ↑ DeSoto's Florida Trails - retrieved 5 September 2008

- ↑ Pousner, Howard, "Fernbank archaeologist confident he has found de Soto site," Atlanta Journal-Constitution, November 6, 2009.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 ""The Old Mobile Project Newsletter"" (PDF). "University of South Alabama Center for Archaeological Studies". http://www.usouthal.edu/archaeology/pdf/issue-17.pdf. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Higginbotham, Jay (2001). Mobile, The New History of Alabama's First City. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press. p. 10. ISBN 0-8173-1065-7.

- ↑ Carter, Cecile Elkins. Caddo Indians: Where We Come From. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001: 21. ISBN 0-8061-3318-X

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Charles Hudson (1997). Page 349-52 "Death of de Soto".

- ↑ Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism. "Hernando de Soto Historical Marker". http://www.stoppingpoints.com/louisiana/Concordia/Hernando+de+Soto.html. Retrieved August 9, 2009.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Robert S. Weddle. "Moscoso Alvarado, Luis de". Handbook of Texas Online. http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/MM/fmo71.html. Retrieved 2007-11-22.

- ↑ Josephy, Alvin M., Jr. (1994). 500 Nations, An Illustrated History of North American Indians. New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 142–149. ISBN 0-679-42930-1.

- ↑ Josephy, Alvin M., Jr. (1994). 500 Nations, An Illustrated History of North American Indians. New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 152–153. ISBN 0-679-42930-1.

- Clayton, Lawrence A. Clayton, Vernon J. Knight and Edward C. Moore (Editor): The de Soto Chronicles: The Expedition of Hernando de Soto to North America in 1539-1543; University of Alabama Press 1996. ISBN 0-8173-0824-5

- Duncan, David Ewing: Hernando de Soto: A Savage Quest in the Americas; University of Oklahoma Press 1997. ISBN 0-517-58222-8

- Hudson, Charles M., Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun: Hernando De Soto and the South's Ancient Chiefdoms, University of Georgia Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8203-1888-4

- Albert, Steve: Looking Back......Natural Steps; Pinnacle Mountain Community Post 1991.

- Henker, Fred O., M.D. Natural Steps, Arkansas, Arkansas History Commission 1999.

- Jennings, John. (1959) The Golden Eagle. Dell.

- MacQuarie, Kim. (2007) The last days of the Incas. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-6049-X ISBN 978-0-7432-6049-7

- Maura, Juan Francisco. Españolas de ultramar. Valencia: Universidad de Valencia, 2005.

- "American Conquest, The Oldest Record of Native America". http://www.floridahistory.com/inset44.html. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- "The De Soto Chronicles Volume I, by Clayton, Knight, & Moore 1994" (PDF). http://www.nps.gov/archive/deso/chronicles/Volume1/toc.htm. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- "Florida of the Inca, Garcilaso de la Vega, el Inca 1539-1616". http://www.floridahistory.com/inca-1.html. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

External links

- Hernando de Soto in the Conquest of Central America

- Research to Reconstruct the Route of the Expedition

- De Soto Memorial in Florida

- floridahistory.com has it wrong Discussion of a Disputed Portion of the de Soto Trail

- City of Hot Springs City of Hot Springs Official Website

- National Park Service, Hot Springs National Park • U.S. National Park Service website

- Hot Springs history and facts